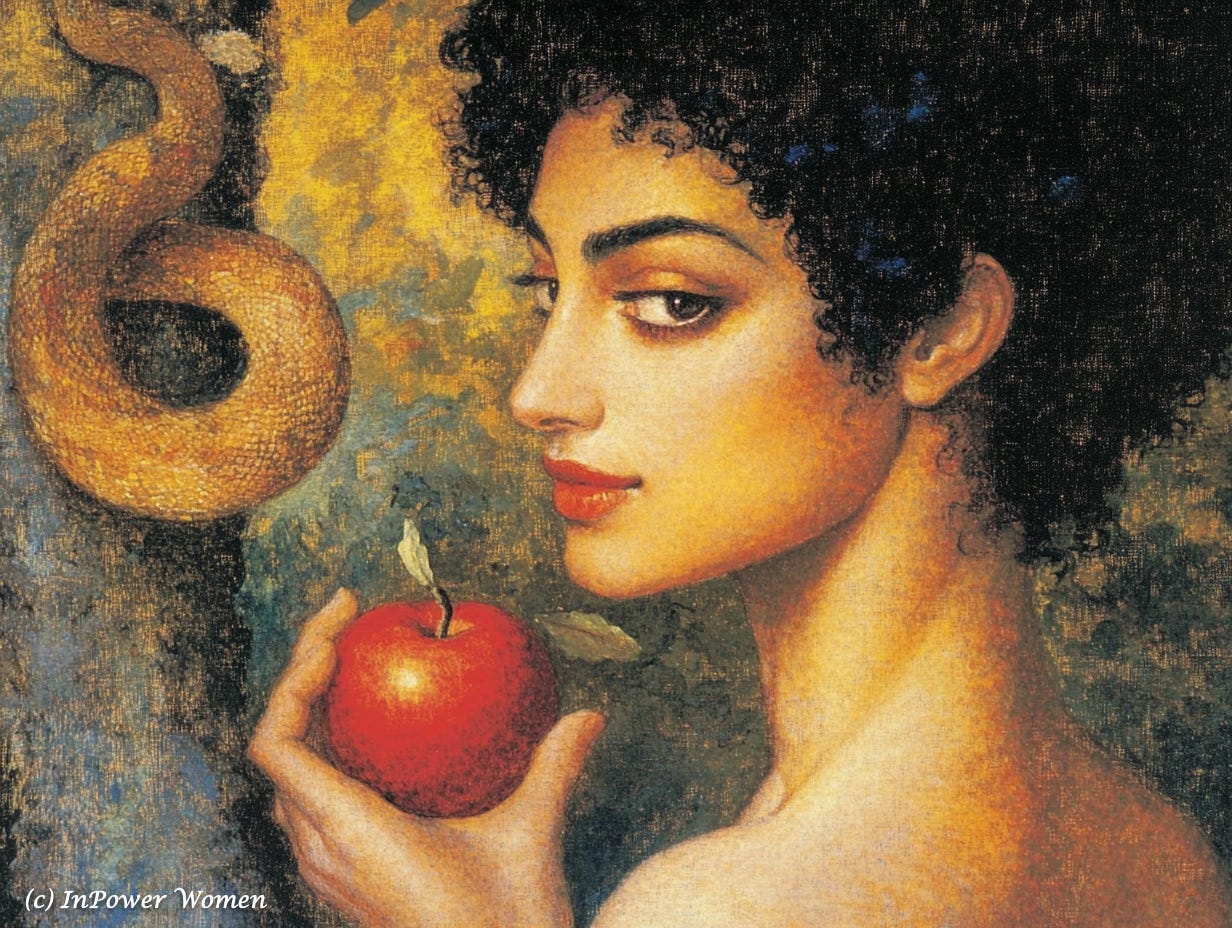

Eve As The Archetype Of The Modern Woman

Background to the Manifesta “Reimagining Eve: Healing Women’s Broken Relationship With Power”

Why did I choose the mythical character of Eve as my archetype of the modern woman for purposes of exploring ways to empower real women today? As I explained in my Manifesta, Eve is much more than a religious reference, she is an allegorical figure whose story has been used directly and indirectly for over 3,000 years to justify excluding women from leadership, treating them as property, and abusing them in the systems of governance that gave rise to our modern western institutions of civil and religious law. As importantly, interpretations of Eve twisted what may have been an originally empowering vision of human beings into cultural stories that excused men for their irresponsibility and blamed women for being too powerful—so that men were unable to resist their temptations and were expected to take our power in order to protect themselves.

While today’s mythical women, from Katniss Everdeen (Hunger Games) to Ilsa (Frozen), are more empowered and empowering, the cultural leading lady stories adult women carry inside us about what makes a powerful woman stem more from the stories our parents and grandparents were told, and tend to harken back to dramatic characters that look more like Lady McBeth or fairy tale figures like Cinderella and Snow White. It is these stories still embedded in the culture that fuel social pressure for women to be perfect, take few risks, subvert our desires, and place ourselves second. Most of these cultural archetypes can trace their roots back to Eve, who quite literally painted the picture of the first woman, from whom most other modern female archetypes emerged.

Since these stories of what makes a good and bad woman find their roots in Eve, we must explore her story to retell our own.

Eve’s Story Isn’t The Story We Know

I was not raised in a religious household. I never went to church, synagogue, or mosque to learn the story of Eve. But my parents were both raised in fundamentalist Christian homes, and I learned the same story I later found that my religious compatriots learned: Adam was the first human. Eve was created from his rib. They were told to eat of all the fruit of the Garden of Eden, except for the Tree of Knowledge. The snake, who was really the devil in disguise, tempted Eve with the apple from the Tree of Knowledge. Eve ate of the apple and shared it with Adam, who also ate. They became knowing, including knowing themselves as sexual creatures, and knew shame, covering themselves. God discovered they had disobeyed his orders and cast them out from the garden, damning Adam to work for a living and Eve to suffer the blood and pain of procreation.

In this version of the story, Eve was the original sinner and tempted Adam into sin, which included the desire to learn and be a sexual creature. As a result of Eve’s “treachery and disobedience,” the entire human race is poisoned with her sin. She has damned us all. The only redemption for a woman is to eschew her Eve-like curiosity and sexuality and channel her energy into being the perfect mother, supportive and nurturing of her children and her husband. Her penance is to never challenge the men she is responsible for damning.

My parents told me they didn’t believe this story, but once I heard it, I saw it reinforced through their beliefs and the messages I received from the cultures I grew up in, from the Midwest to the West Coast and the East Coast of the U.S. As I grew into adulthood and parenthood myself, I struggled with beliefs in the workplace that I had to be more than perfect to succeed, that I could not anger men (or be angry) without threatening to sideline my career, and that being perfect at work was not enough if I could not also be perfect as a mother to my children and a wife to my husband. In my personal life I struggled with messages about my sexuality that shamed me for feeling desire, even when surrounded by media images of women as enticing/entrapping sexual creatures, and beliefs about personal power that encouraged me to play small.

When I became an executive coach, I saw these same stories play out in my female clients, forcing on them greater psychological burdens in their journey to success than any male I knew or supported.

I became curious. I studied history to learn where women’s self-repression originated, and I learned that the repressions on women that I experienced had existed for thousands of years, echoed in Eve’s story. But even before the Bible vilified Eve, 25% of the Code of Hammurabi and 52% of the Code of the Assyrians addressed restrictions on women in the context of slavery and marriage. For reasons I still do not completely understand, human beings have felt the need to restrict and control women’s lives and bodies since laws began being recorded. With this heavy burden of history, it’s no wonder women and men have assimilated these beliefs into what they assume is true of people wearing women’s bodies. Eve was just the most recent in a long line of stories about why women were dangerous and needed to be controlled in the first systems of law and governance.

Reading theological scholar Elaine Pagels, I also learned that the story of Eve in the Bible, which had been around long before it appeared there, had been interpreted in many ways other than the story I’d heard. And most of these interpretations prior to 410 C.E., rather than condemning women and men to shame and guilt, had been intended as a story of freedom. In its original interpretation, Eve’s tale told of human beings rising above and freeing themselves from the baser drives of nature to grow beyond the innocence of the garden into free will over the choice between good and evil.

To many early Christians, the metaphor of the Tree of Knowledge was awareness of choice, and that by eating of the apple, unlike animals, humans—led by Eve, rather than damned by her—matured into the understanding that they could see the difference between good and evil. In these interpretations, Eve gave humanity the power to choose good over evil and create the human race with the maturation of their minds and bodies into adulthood and sexuality.

Eve As Political Tool

The image of humans as empowered creatures capable of individual free will to choose good over evil, potentially capable of self-governance, was very attractive to early Christians who the Roman Empire persecuted. The alternative reading of Eve’s origin story, the one where she empowered humans with the fruit of knowledge, fueled early Christians to persist with courage through the early centuries after Christ’s death when they were cruelly victimized. But with the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity in 312 C.E., the Church exited its persecution status to align with the rulers of the day. Church leaders and their patrons in secular government began to find ideas of self-governance less attractive than the idea of a Christian Emperor divinely empowered to rule autocratically.

Painting Eve as the temptress who, in cahoots with the devilish snake overpowered the unwitting Adam into sin, Augustine of Hippo reinterpreted the existing, empowering, theological doctrine in 410 C.E., inventing the doctrine of original sin to blame all of mankind for the sins of their first mother, Eve, and their first father, Adam.

In Augustine’s telling, cast as the original sinner, Eve’s myth became the rationale for why human beings who carried the blood of Eve and Adam could not be trusted to choose good over evil and why human Emperors—however flawed—who were appointed by God must rule them. Augustine also used his ideas of original sin, which can be found nowhere in the Bible itself, to justify stripping women of the power they had begun to gain in the early Christian Church as leaders of spiritual thought. In Augustine’s theological writings, Eve’s crime damned all women to perpetual servitude to men. Only in the role of a sexless and passive mother, like the Virgin Mary, might women be spared damnation.

Even in his own time, Augustine’s ideas were not universally accepted. Scholars debated his interpretation of original sin vehemently for over a century until the Council of Orange codified it in 529 C.E. As Pagels writes in Adam, Eve and the Serpent, “Augustine’s theory of original sin not only proved politically expedient, since it persuaded many of his contemporaries that human beings universally needed a controlling government— which meant, in their case, a Christian state and an imperially supported church—but also offered an analysis of human nature that became, for better and worse, the heritage of all subsequent generations of western Christians and the major influence on their psychological and political thinking.”

But Eve’s political utility to those in power went beyond merely justifying the reason for autocratic governance; her crime became the rationale for removing women from leadership and controlling women’s bodies, needs, and desires through time, including burning women as witches or merely blaming them for all the ills men suffer, as documented in the book Resurrecting Eve (Pughe & Sohl):

“Woman is more carnal than man: there was a defect in the formation of the first woman (Eve) since she was formed with a bent rib. She is imperfect and thus always deceives. Witchcraft comes from carnal lust. Women are to be chaste and subservient to men.” (Rev. John Robinson in condemning witchcraft - 1575-1625)

”(Eve’s) disobedience triggered Adam’s, and produced the chain reaction of anxiety and guilt in every person and the estrangement between man and God, man and woman, brothers, nations and races, that continues to this day.” (William Barker, 1966)

”(Eve) did not accept her position in the God-given hierarchy; she perverted her role as a helper by luring her husband to transgress God’s command, and thereby brought ruin upon herself and mankind.” (Folke T. Olofsson - 2001)

Whatever Eve’s original story was, it’s clear that it has been used as a political tool in recent millennia to deprive women of both the actual power they carry in their bodies, hearts, and minds and their potential power as leaders in society.

Eve’s Real Story

There is a lot of really interesting discussion and debate—by historians, theologians, women of faith and others like me perusing their works—about all the potential variations of Eve’s story prior to becoming enshrined in the political history of the Western world through religious and theological interpretation. These discussions contain much more empowering and relevant-to-modern-women ideas about what Eve as an archetype of feminine power might have meant to the people who created and retold the stories of her.

I haven’t read it all and will continue to share what I learn as I explore strategies for reimagining Eve. But here are a few ideas that really intrigue me about how we can see ourselves and our power more readily and healthily through the myth of Eve as I start out on this journey:

At the time Christianity was becoming institutionalized, the snake was a commonly understood symbol of the lifegiving, transformational fertility goddess. When the Church fathers demonized the snake in Genesis, this was a symbolic attempt to shame women from association with their sexuality and fertility—not to mention the rival spiritual sect of paganism. It was part of their intentional effort to subvert the traditionally female god with a male version. The result has been to use Eve’s story intentionally over the centuries to limit a woman’s sexual expression to motherhood. (The Creation of Patriarchy, G Lerner.)

Early Christian Gnostics viewed Eve as the authentic spiritual self (similar to the Holy Spirit) found within the soul of all human beings. Removing Adam’s rib to become a whole being (Eve) was viewed as a symbolic strengthening and honoring of our spiritual selves. The spiritual and physical union of Eve and Adam, then, became the soul’s reconnection, which all humans crave. (Adam, Eve and the Serpent, E. Pagels.)

In line with the point above, “Adam” was not a person’s name in the ancient Hebrew, but a word for “human” (ha-adam), and rather than removing a rib bone, the word “tsela” in ancient Hebrew indicated more of a portion of the human, the feminine/spiritual dimension. In this reading, the original human, ha-adam, was whole and genderless, but in separating the feminine dimension became two gendered beings. (Resurrecting Eve - Pughe & Sohl)

The origin story I learned told of Eve secretly plotting with the snake to deceive Adam. However, the actual text of Genesis 3:3-7 says that she talked to the snake, and “…took some of its fruit and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her and he ate it.” This painting of Adam as a passive victim doesn't really add up if he participated in the whole thing. (Resurrecting Eve - Pughe & Sohl)

Augustine came to the idea of original sin, and the blaming of Eve for tempting Adam with sexual knowledge, in part because he felt himself to be a helpless slave to his own sexual desire, as described in his Confessions, “against my own will…I was not, therefore, the cause of it, but the ‘sin that dwells in me’: from the punishment of that more voluntary sin, because I was the son of Adam.” In his later work, De Civitate Dei, Augustine expands on the theme of sin to damn all humans with sin originating in their blood and genetic code, “For we all were in that one man, since all of us were that one man who fell into sin through the woman who was made from him.” (Adam, Eve and the Serpent, E. Pagels.)

Finally, in my exploration to date, one particular reality stands out to me about how to see Eve’s story through a new—more empowering—lens. Eve and Adam’s story has been used to shame women through time for being sexual creatures, though such shame messages don’t apply equally to men, representing the first of many double-standards. It was not until after the original humans left the garden that they could have children, which begat the human race.

The garden being a place of innocence leads me to believe that in the garden, Eve and Adam were metaphors for children, proto-humans untroubled by the need to make a living and untormented by hormones. They were literally lorded over by a paternal being who set out rules for what they could and could not do (i.e., eat the apple) or know of the complexities of the world (i.e., know about sex or good and evil.) Once they matured physically and mentally (becoming capable of knowledge and morals), Eve and Adam began to bear the burdens and joys of adulthood, which included the need to make a living and create the human race. This, of course, meant that their years of innocence, living in the “paradise” of childhood, was over. Thus, humanity learned the same thing at the beginning of time that we continue to learn today.

Adulting is hard.

But adulting also brings with it great joys and opportunities. The battle to be good and manage what feels like evil within and around us creates meaning and purpose that drives us to love more deeply and accomplish great things.

Eve was the figure that led humankind into this adulthood full of pain and pleasure, risk and opportunity, joy and the sorrow that makes joy more poignant and precious. As Roberta Pughe and Paula Sohl point out in Resurrecting Eve, “(Eve) is the first independent woman. Her crime? Self-expression and self-determination: a testimonial for all. She was a woman courageous and powerful enough to assert herself in the face of pure, male authority.”

So for me, Eve has become an archetype worth reimagining, and in so doing crafting an opportunity for every woman to consider revising, reimagining, and retelling her own story.

That’s what I hope we can do together here on InPower Women, reimagine Eve and inpower ourselves as we do so.

Updated: March 19, 2025

Dana Theus

Executive Coach

InPowerCoaching.com

Connect with Dana on LinkedIn

This is really insightful. And I totally agree. Eve isn't just the first sinner but the first independent woman

I learned so much about Eve in many contexts, thanks